Google, borders, crises, and Tamara Kametani

At the beginning of the period of self-isolation, I came across a video by Tamara Kametani on Facebook about her work Total Security Life, which is actually an advertisement for a fictitious company that builds walls and border barriers. The perfect landscape of the blue lake and rippling trees is surrounded by a high grey wall, above which an eagle flies freely in the rays of the sun. We should buy the wall to protect ourselves. But from what? What are the threats for which we are building walls? Today, we really need walls and borders temporarily, but it can easily happen that we start dividing people into those in front of the wall and those behind the wall, into “us” and “them”. The walls embody the authority of fear, which we are so happy to be defined by. I wonder what will happen if we adopt this definition. However, Tamara’s approach keeps its distance, which calms us in this perilous situation. How does she perceive this?

Tamara Kametani is a Slovak artist who lives and works between London and Athens. In her work, she deals with the topics of border policy, surveillance, the Internet and the distribution of technology. She is particularly interested in the role that technology plays in creating contemporary and historical narratives and the new experiences it facilitates. In her work, Kametani responds to complex questions arising from the complex relationship between aesthetics and politics. She studied at the Royal College of Art in London, where she obtained an MA in Contemporary Art Practice. She has had several solo and group exhibitions, including Walls 2.0 – Augmenting border reality at Elephant West Gallery in London, For the Time Being, curated by the Royal College of Art at Photographers’ Gallery in London, 404 – Resistance in the Digital Age with the RAGE collective at the Centre for Contemporary Chinese Art in Manchester, and [ENTER] at the Triennale of Photography in Hamburg. She has received various residencies, including the British Council’s residency in Athens, Connect for Creativity, and the artistic residency of the Florence Trust.

In your work, you reflect on current issues, offering a new perspective on them, which certainly requires thorough research on such topics in the media. What role does this play in your work?

My process is very organic. I usually start being interested in a topic that I want to better understand. I wouldn’t feel confident if I had to work on something I don’t understand. And so I have to do quite extensive research, which sometimes makes up 80% of the whole process. But it can be the most exciting part! I often have no clear idea at the beginning about what the work will look like and what medium I will use. It mostly transpires only in the research process, which one is the correct and appropriate one. I often work with materials and media in which I’m not an expert, so part of the research is also about getting acquainted with the medium itself.

Many of your works deal with the refugee crisis. What led you to this topic?

When I started addressing this topic in 2015, there was a lot of talk about it and it was extensively covered in the media. Again, it was an organic process based on my curiosity. I wanted to understand what exactly, why and where it’s happening and how it affects Europe. That crisis is called a “refugee crisis”, but in reality it’s a European crisis. Refugee crises are happening more or less all over the world all the time, but since it started to affect Europe more, we have considered it a crisis. I was wondering if it was possible to see ships crossing the Aegean Sea from Turkey to the Greek islands, which were in the media constantly at the time, on Google Earth. At that time, there were dozens of them a day. I quickly discovered that Google Earth had no real view of the seas and oceans around the world. Instead, there is a computer-generated animation of ripples that move slowly in the gentle breeze across the sea. There are no ships, tankers, nothing real.

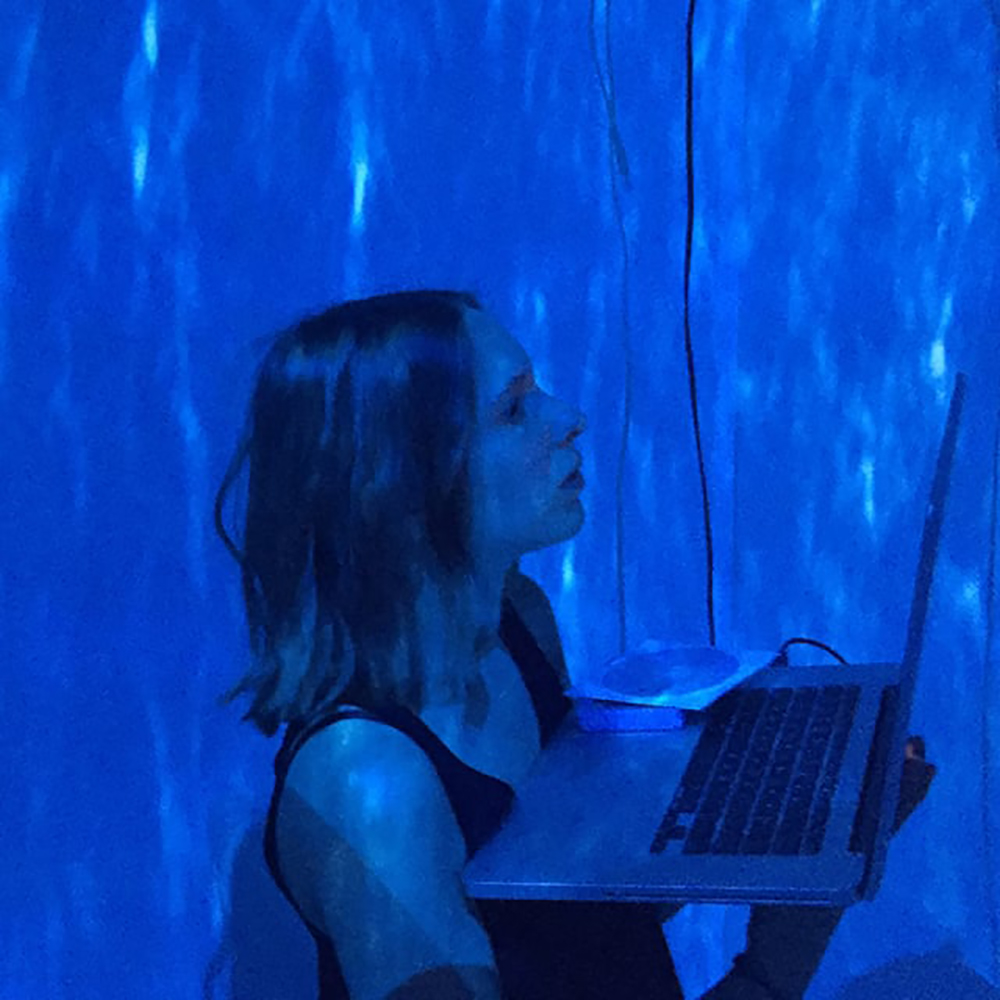

That caught my attention, and I started working on it. Eventually, it led to the installation The sea stayed calm for 180 miles, which combines two elements: a Google Earth live stream, showing a part of the Mediterranean between Libya and Lampedusa, and a bench made of wood from ships on which migrants crossed this section of the sea. In one space, these two elements depict two diametrically opposed versions of the sea and point to a hierarchy of digital and physical experiences, but also to the relationship between observation and participation.

So you realised the discrepancy between what’s happening in reality and what’s being presented through Google Earth?

Basically yes. Google is such a huge company that it has embedded authority. You consider the information you receive from it to be true. When you need to find a route, you look at Google Maps and you believe it. If this weren’t the case, people wouldn’t use Google products. The Mediterranean Sea has some of the busiest shipping routes in the world. By replacing this space with fiction, Google not only aesthetises it, but also presents it as a depoliticised space in which no state jurisdiction, or the responsibility related to it, play a role.

You’ve used Google products in several of your works. Why Google?

I have such an ambivalent relationship with Google. I try to take the protection of my online privacy seriously, but even though, for example, I don’t use Google Chrome, I use Gmail and Google Maps, I voluntarily give my data to Google. I could change that, but their products are actually convenient and I’m somewhat dependent on them. On the other hand, because they have such a large impact, they have an infinite amount of data from their users, which is problematic.

Harvest is Every Day is another work that only exists thanks to Google Street View. It consisted of me physically trying to get into as many Google Street View images as possible. It was like some sort of a lo-fi fight with a technology giant such as Google, but also a legal hack of their maps in a way, realised by my physical presence, as it’s the only thing I have left. It’s almost impossible to avoid surveillance today, and if I cannot get around it, I will at least be in control. I will physically create my digital footprint and the camera will not capture me when I’m not prepared for it.

I have a feeling that the connection between the chosen medium and the communicated topic is often based on a kind of discrepancy between one and the other in your work. It is as if it benefitted from the improbability of that connection. A certain irony and humour could be perceived behind this approach. What role do they play for you?

It’s important for my work to sort of reverse the original purpose of the media I use. I call it “trickery”. Some kind of razzle-dazzle. From the visual side of my works, you would expect them to be about something other than what they really are. Usually, my work requires the viewer to stop for a second. That’s the trick. For example, the installation The sea stayed calm for 180 miles is physically very comfortable. The whole thing is blue; it’s nice to look at. If you don’t stop, you can leave with the feeling how nice it was and how comfortable it was to sit there. But in fact, the content is about something completely different and not pleasant at all.

I really like humour in art, but it’s one of the hardest things – making art that’s both funny and serious. Although I’m still far from humour, some of my work has a degree of irony. For example, the installation Total Security Life talks about the desire to be safe, about protection, about how we deal with threats, real or those that are passed on to us. But, formally, it looks like a company presentation at a trade fair. This fictitious company specialises in security solutions, selling various types of walls and fencing, as well as those built by governments at borders. In its rhetoric, the company uses people’s fear and uncertainty about safety to justify the construction of these walls. The existence of such a company is clearly absurd, but at first glance it looks serious and like a real company you can trust. The element of irony is probably based on the fact that we now live in such a world.

You work with the aesthetics of advertising and marketing of large companies and corporations. Why did you choose this kind of form in particular?

I’m fascinated by the language and strategies of marketing and advertising because they work. Many contracts for border walls and fencing are implemented by large companies operating in transnational projects throughout Europe. It’s not easy to find out that they also construct border walls. On their website, they promote projects such as the reconstruction of an opera house or the construction of a new station. On the other hand, companies that specialise in security solutions use very vague language that doesn’t say what exactly those security solutions are. They only say that they are important for maintaining safety, while dealing with the topic of family, children, values, the future. It appeals to human fears and insecurities. These are the empty words that are there to create an atmosphere that should make you believe that this is exactly what you need.

Where does your interest in the topic of borders come from? Does it affect you personally?

My work usually results from events that happen where I live. I perceive Europe as a whole rather than as individual countries, so the borders of Europe affect me to some extent. I often move from place to place, but the borders I deal with in my work – the border walls and the liquid border of the Mediterranean – do not concern me personally because I have a European passport.

I flew to Lampedusa to source the wood from which the bench in the installation The sea stayed calm for 180 miles is made. There the ships on which the refugees sailed are dumped at a kind of “ship cemetery”. Refugees, mostly from sub-Saharan Africa, whom I met at Lampedusa, asked me how I got there and how long it took me to travel. I said by plane and that it took a long time – the whole day. Some of them were surprised at how easy it was for me to get there. My situation is completely different from the situation of a very large number of other people.

In addition to Total Security Life, you also deal with the topic of borders in another work, Walls 2.0. How do you look at boundaries and physical barriers in this work?

When I was working with my technical collaborator on a video for Total Security Life, we thought it would be interesting to use the wall physically, to convey the experience of the presence of this barrier. Many people have this experience, but many do not. So we created an augmented reality mobile application in which you see a virtual wall. The application is intended for groups that are separated by this wall. So, on the one hand, it’s about how the individual copes with this wall in a physical environment, and also about the group dynamics that people experience together.

Recording from the Walls 2.0 app. You can download the app to your Android phone here. We will add the link to the app in the App Store as soon as it will be approved and available.

How did the presence of the wall affect people’s behaviour?

A kind of gathering formed on each side of the wall – by being separated, they have something in common against those on the other side. While presenting the work, I noticed that the wall has intrinsic authority, even if it’s only virtual. Although we included certain authoritative elements directly in the application – it incorporates warnings that you’re too close to the wall, you’re in a danger zone, you will face legal consequences, etc. However, in reality, people, even though they could cross to the other side (because the wall was just virtual), they didn’t do it. Again, this concerns the fear of danger and how this fear can be abused in an authoritative way.

Now that you are in the research phase again, what are you working on?

I’m currently working on a project that is part of an online residency with Off Site Projects, but I don’t know yet what its next life will be like. I’m researching how digital surveillance methods are changing in the current pandemic. In many countries, measures and applications have been put in place to reduce the number of infected people, but at the same time using technologies that are controversial in terms of privacy. In Europe, thanks to the GDPR, this is more or less done on a voluntary basis, but in China, South Korea and Israel, these methods are highly debatable.

Otherwise, this is very much an example of how I do research: something’s happening, and instead of worrying, I’m doing something that’s useful to me. To prepare for the future. It’s probably my way of keeping it together in this precarious situation. Haha.

TRANSLATION Lucia Udvardyová