Jennifer Walshe: I’m a composer and artist rather than a philosopher

Jennifer Walshe is one of the most original composers of contemporary music. Her works prove that music doesn’t have to be only about sensations and feelings, but that it has a lot to say about the world we live in. A Slovak audience had the opportunity to see the Irish composer, singer and artist, whose work ranges from historical mystifications to conceptual experiments, at the Next festival in Bratislava last year, and her compositions have been performed and broadcast across the globe.

Walshe’s recent projects include Historical Documents of the Irish Avant-Garde (2015) – a fictional history of the musical avant-garde in Ireland spanning 187 years. The project was presented under the umbrella of the Aisteach Foundation, a fictional organisation that serves as an “avant garde archive of Ireland”. In 2007, Walshe started to work on the project Grúpat, a fictional artistic collective consisting of 12 different alter egos who create various compositions, installations, graphic scores, films, photographs, sculptures and fashion items. EVERYTHING IS IMPORTANT (2016) is an interdisciplinary composition for voice and string quartet, accompanied by a film. Another important work is the opera TIME TIME TIME (2019) for nine performers, which was written in collaboration with the renowned philosopher Timothy Morton.

Moreover, Jennifer often performs as a vocalist, specialising in various extended vocal techniques. She has written a number of compositions for solo voice or voice accompanied by other instruments. Jennifer Walshe currently works as a professor of experimental performance at the State University of Music and the Performing Arts in Stuttgart.

It seems to me that your works have a certain sociological approach. You connect various elements, look at them from “above” and then explore either the way we perceive history or the way we look at technology and challenge them, putting them in new contexts. But at the same time, you said that you’re not doing philosophy through music. What do you mean by that? Doesn’t the new way of thinking you’re proposing to the listeners and viewers also suggest a certain philosophy?

I’m a composer and artist rather than a philosopher. Having worked with people like Tim Morton closely, and having also seen how involved theory and philosophy has become in art, I just want to make the gentle case that I’m a composer and an artist doing my work, and while it may embody a certain philosophy, or may be read in philosophical terms, I’m not setting out to do that myself. I’m not trying to demonstrate theoretical concepts. At the core, I’m trying to pay attention to life, and my work reflects that attention.

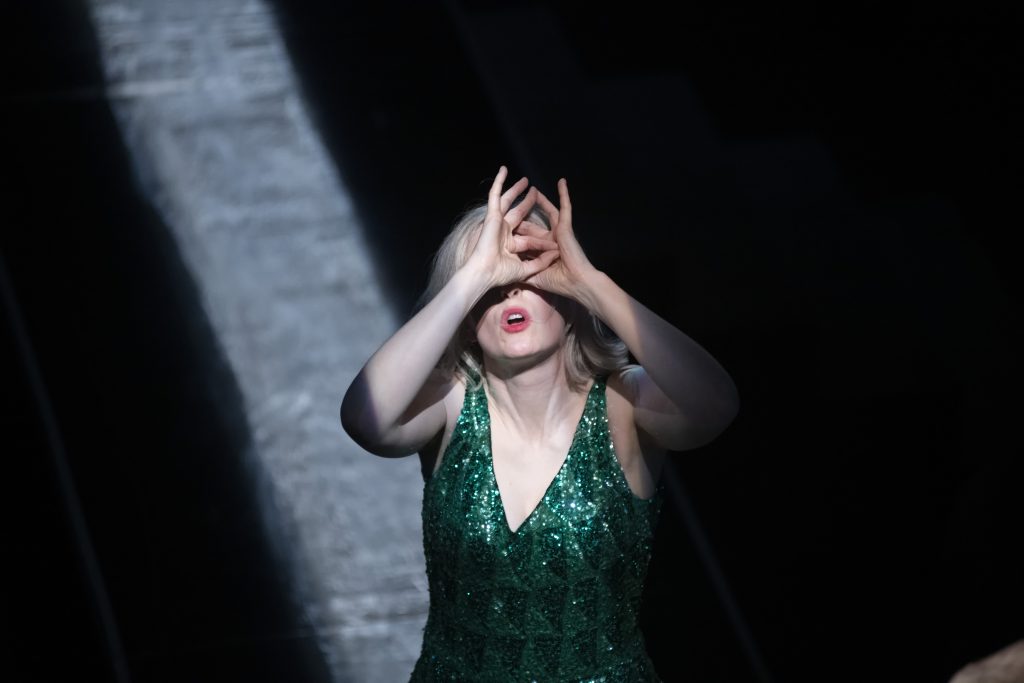

The Opera TIME TIME TIME © Signe Fuglesteg Luksengard courtesy of Ultima Oslo Contemporary Music Festival

Often people are worried that technologies are actually controlling them, instead of them having control over technologies. In some of your works, for example in Is it cool to try hard now, you’re using what you call speculative AI. By learning about AI and then creating your own results for what would possibly be the results of AI learning, you find yourself in a position in which you can be the one who controls this. Do you think this gives you some kind of control over the new technologies?

Technology is completely embedded in every element of our lives, but often don’t even recognise or question it. The moment we start paying attention to the technologies around us, we start to gain some control, even if it is only a very small amount of control. We have a moment of weirdness where we can see in stark relief, for example, how astonishing it is that we take out our phones to check where the subway stop is and in that moment our phones our in contact with three satellites in geosynchronous orbit with the Earth, that we are a node in a vast system of corporations and infrastructures which make sure we get to the concert on time.

A great deal of my work is essentially science fiction – I’m telling stories about life, with science and technology as the filter through which I’m viewing things.

In this age in which sci-fi is becoming a reality, do you derive inspiration from any science fiction authors?

I have always been a massive sci-fi fan. There are many works of mine which function as sci-fi stories, such as THE CHURCH OF FREQUENCY & PROTEIN and The Legend of the Fornar Resistance1. But in a way a huge amount of what I do is a form of sci-fi, it’s just simply that I’m positioning the works in the present day, or present day-ish, rather than the future. William Gibson talks about using sci-fi to understand the world we live in now using the sci-fi tool-kit to talk about what it’s like to be alive today. I think authors like Ursula Le Guin or Ted Chiang or N.K. Jemisin look to explain the world around us, even when they’re ostensibly dealing with another universe.

You have already mentioned the philosopher Timothy Morton, with whom you also wrote the opera TIME TIME TIME2 together. How did this collaboration start? Was the original idea to have Timothy sitting on the stage in a yoga-like pose during the performance?

It was probably Drew Daniel who introduced me to Tim’s work. I was reading Hyperobjects in 2016, when I was working on EVERYTHING IS IMPORTANT3, and it was resonating with a lot of what I was thinking about, so on sheer human impulse, I wrote to Tim. He wrote back and suggested we Skype, and then we met in Copenhagen when Gong Tomorrow brought him over so we could do a discussion about the intersections between our work as part of Gong Tomorrow’s performance of EVERYTHING IS IMPORTANT. I had been thinking a lot about time and the idea of writing an opera about time, and Peter Meanwell wanted to commission the opera. I suggested Tim as a collaborator (they had been on the most recent Dark Ecology tour) and that’s how it went. Very human, organic connections, reading someone’s work, reaching out to them, seeing it would work.

The idea of Tim onstage came during the process. I thought what if he just meditated the whole time. He would be the first to tell you it’s a huge challenge! And the musicians… during the dinosaur scene they often come very close to him and blast their instruments at him to try and jolt him, this internal play the audience aren’t even aware of…

At the end of the performance, all of the audience members were given a tiny fossilised ammonite. Were you also thinking about any other objects to give to the audience?

Oh, you should have been given that at the beginning of the performance! I felt it was really important that everyone in the audience be given a tiny fossil to hold in their hand, to try and make contact with the sense of deep time4. You’re holding a tiny being in your hand that lived around 240 million years ago. Maybe, if you hold it for the roughly 80 to 90-minute duration of TIME, and you concentrate really hard, you might be able to make contact with that as a fact – that creatures lived here 240 million years ago, that we humans have been here on Earth for such a brief duration.

A film still from AN GLÉACHT, Caoimhín Breathnach & Jennifer Walshe

As part of my research for TIME I interviewed Professor Paul Barrett, one of the most renowned palaeontologists around, at the Natural History Museum of London. I spent a lot of time in natural history museums while I was working on the piece, particularly in the NHM (because it’s in the city I live in). What struck me was how little time people spend with dinosaurs, or meteorites, or really old things. They walk by Sophie the Stegosaurus in the NHM, maybe pause for a maximum of 30 seconds, snap a pic, and they’re gone. The Royal Observatory has a piece of a meteorite at the entrance, you are allowed to touch it, and there’s a sign saying it’s the oldest thing you’ll ever touch. People run their hands over it and rush on for the main attraction. It takes time and concentration to get in contact with deep time. When I spoke with Professor Barrett, I asked him what objects he might recommend the audience could touch, and he recommended ammonites because they’re freely available, and ethical – you won’t be depriving a museum or researchers of important specimens (Did you know there’s a black market in dinosaur bones? Well, there is!).

In your work A Late Anthology of Early Music, Vol. 1: Ancient to Renaissance, you try to map the temporal development of the neural network’s learning and understanding of your voice onto the history of Western early vocal music. This is a very interesting idea. Did you find any similarities or shared patterns between the historical development and AI’s learning process? What new perspectives could this new proposal for thinking about Western music offer us compared to the “official” history of music?

I spent many years teaching western classical music, and you teach a very clear story. You generally begin with plainchant (despite the fact there was a great deal of music which preceded it) and focus on this linear development of harmony, from monophonic simplicity through the polyphonic complexity. It struck me, when I listened to the AI-generated files which were trained on my voice, that there were similarities, as I heard the network move from long notes on a single pitch to more complex constructions.

To produce any output from a network, a selection has to be made of what material the network will be trained on. And this is where the network immediately becomes biased, where exclusions are made, where racist or sexist or homophobic material is integrated without AI researchers paying attention to what’s happening. It’s a parallel process to what happens in education – when we make a canon of western classical music and say “these are the best pieces, the most representative pieces of the period 500 to 1500” biases and exclusions creep in instantly also. I want people to always question the archive, to question what’s there and why, what’s excluded and why.

I love archives. I love libraries. I love what they represent, and I love the imaginative spaces they create for us as humans, the way we can dream material into them. Part of that dreaming is seeing what’s not represented, what’s been excluded, and opening the archive, decolonising it. Whether it’s a library, a playlist, or a corpus of training material for an AI, the material we choose to include or exclude has real-world implications for all of us.

Is this also the case in the Grúpat project, dreaming stories about your alternate identities? And what about Aistech and the An Gleácht film? Is this about dreaming stories about the past? Did you also work with any real archives in this case?

Grúpat was about creating an archive of people I would have loved to exist and work alongside. They’re all within five years of my age. It was also about freeing up anybody’s expectations of the sort of music I would write and allowing myself to dream new musics through the people.

Aisteach was a very deliberate act of completely re-writing the past, or maybe in an occult sense “summoning” a different past into being. It is a post-colonial project, which looks at the ramifications of the colonisation of Ireland. For Aisteach, I visited different archives, looking for evidence of the people I was writing into being, seeing if I could find any traces. The Contemporary Music Centre of Ireland’s holdings were important. But probably the archive that has influenced me the most over the years is the Irish Folklore Collection at UCD in Dublin. When I first visited, I had to wear white gloves and only write with a pencil, now, only 13 years later, they’re digitising everything and I can look at it all online. It’s wonderful!

What was your most recent dream?

I was in a massive, multi-layered architectural structure. In a pocket of this structure, high up, I found a shop with old second-hand books and objects (I dream of these sort of shops a lot). Inside, the floor was covered with small cellphone packets with old stamps, but amidst these, I found a packet which purported to be „a child’s commemorative lunch set“, which consisted of a tiny cup, a candle-holder, and a saucer, all covered in garish 1950s-style religious iconography. I snatched it up and wanted to buy it immediately.

Notes

1. The Church of Frequency & Protein (2010) is a composition for voice, trumpet, trombone, percussion, piano, guitar, cello and DVD. The Legend of the Fornar Resistance (2019) is also a book written following the exhibition of the Grúpat project.↩

2.The opera TIME TIME TIME (2019) is a multimedia composition for nine performers (Jennifer Walshe: voice & electronics, Áine O’Dwyer: voice, harp & electronics, Lee Patterson: electronics, M.C. Schmidt: voice & electronics, Eivind Lønning: trumpet, Espen Reinertsen: saxophone, Inga Aas: double bass, Vilde Alnæs: violin, and Timothy Morton); two video screens are also part of the performance. ↩

3.EVERYTHING IS IMPORTANT (2016) is a composition for voice, string quartet and film.↩

4. “Deep time” is a term introduced and applied by John McPhee to the philosophical concept of geological time first developed in the 18th century by Scottish geologist James Hutton. “Deep time” designates the time scale of geological phenomena that is unfathomably greater than the time scale of a human life.↩

COVER Dawid Laskowski courtesy of LCMF Serpentine Galleries