The Social Unconscious Among Videogame Suburbs

The book Ideology and the Virtual City shows what role games play in the process of coping with the pressures of capitalist modernity.

Videogame criticism takes many forms. Apart from analyzing the game mechanics, environments, or narratives, the political frame of video games has recently also been getting greater attention. A big topic in recent decades has been the representation of women and minorities, and the last two years have seen a focus on the material conditions prevalent in the gaming industry. Mainstream media have, in turn, been discussing the effects of gaming on education, behavior, and the perception of violence, while more critical approaches try to show the connection between video game stereotypes and racism or the alt-right.

But what if games offer something more than that, and what if, apart from sexism or violent fantasies, they also tell us something important about the socio-economic system? Since the beginning of the 20th century, critical theory has analyzed books, films, and music from just such a perspective. After all, the psychoanalytic theories of Jacques Lacan and post-structuralism gave critical theory further tools that allowed us to peer beneath the surface of things. They thus allow us to discover the ideational values that might not be apparent at first sight, and these extend further than just an analysis of stereotypical gender roles.

Video games are still rather rare items in the arsenal of critical theory. But it seems that the last few years have seen an upsurge in the interest in video games, and their role as a cultural form has been discussed outside of the spheres of academia or specialized publishing – for example, Jon Bailes’ book Ideology and the Virtual City (Repeater Books, 2019), which has the subtitle Videogames, Power Fantasies and Neoliberalism. In this work, Bailes dedicates 112 dense pages to discussing four mainstream computer games and the way they represent life in neoliberal capitalism as four psychological reactions to its pressures.

Underneath the Virtual City

In his introduction, Bailes explains why he believes that games are a fitting object for studying social critique, writing that “I believe there is also something especially significant in the way that many videogames function as power fantasies, which grant their characters, and through them their players, a sense of agency and control that they generally cannot experience in everyday life [and which] often seem to embody a desire to confront certain boundaries or limitations in society.” Game systems and scenarios always assume a player who will actively move within them. Whether we call it immersion, flow, or the feeling of responsibility, video games furthermore have the capacity to let the player act – despite the fact that such actions take place within a game field clearly defined by the developer’s intentions.

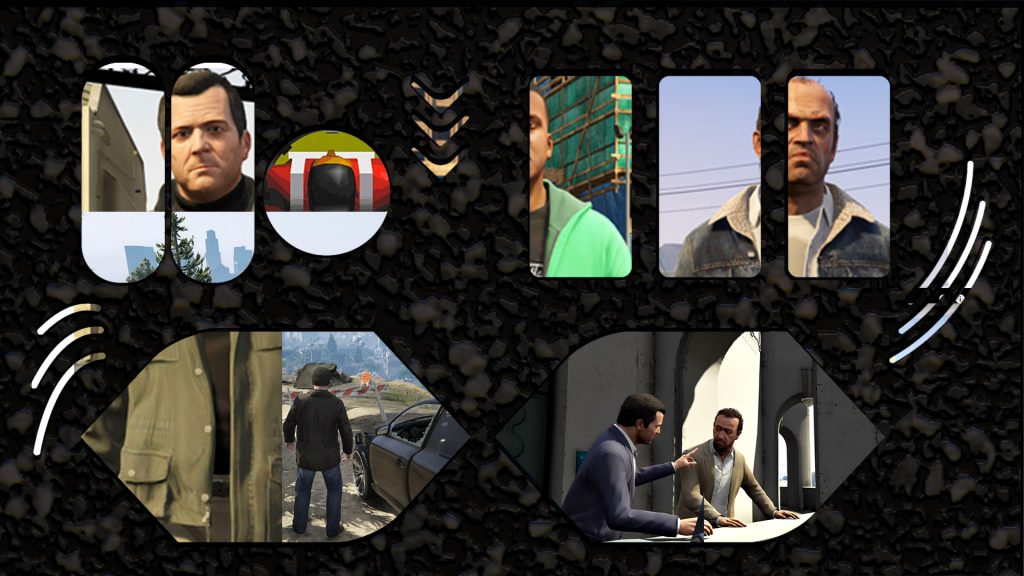

Grand Theft Auto V

Bailes uses the language of contemporary psychoanalysis to draw attention to the fact that the political content present in the games being studied does not necessarily have to be the subject of conscious reflection. Whether GTA V, the Saints Row series, or Persona 5, Bailes agrees with game theorist Alfie Brown when he considers games as vehicles for the unconscious contents that are present in them – in this case, he offers four basic approaches to the present. Alfie Brown and his book Playstation Dreamworld can also serve as secondary reading, as it similarly uses psychoanalysis to describe video games as spaces for the creation of unconscious desires. Bailes’ analysis works from the realization that it is not only about what games show, but also how their internal logics function. What manners of behavior do they celebrate and which ones do they banish, what future is presented as ideal, and what tone do they use to speak about political and economic systems?

In line with leftist theory, Bailes defines neoliberalism mainly through its individualism and the contemporary pressure to meld personal life (work imbues a person with value) with consumerism (the act of buying or enjoying), whose ideals lie in ungraspable extremes. Responsibility for your own success obfuscates social connections, and the limits of the possible are subsumed under the limits of a capitalist society that considers itself the only viable alternative. And it is this limit to which all the titles discussed are oriented.

Grand Theft Capitalism

Cruising through the virtual world of Saints Row IV, where no action has any real impact and all the pleasure and joy is at one’s fingertips, is very analogous to all the pleasures offered by consumer society. The main protagonists of GTA V understand the problematic nature of the system (they even explicitly criticize capitalism), but they still pragmatically play by its rules. Despite adopting a wise-guy ironic distance, the “survival of the fittest” is their watchword, and they serve capitalism’s values in order to keep its wheels rolling.

Both examples are interesting especially because both games present a stylized vision of contemporary society – virtual arenas, or cities that are abstractions of our own reality. Furthermore, the works of Rockstar (GTA) and Deep Silver (the last Saints Row) seem, on the surface, critical towards society. Anyone who has played Grand Theft Auto knows that its world is structured around the unforgiving fight for success and that it is not a beautiful place to live, and that it can be read as a hyperbole and intensification of the injustice that is already present in our everyday lives. However, as Bailes shows, it offers no way out. In both cases, the player’s initiative supports the continuation of the vicious circle of exploitation.

Persona 5

The two other games are more interesting in this regard – the action-adventure game No More Heroes and the RPG Persona 5. The first shows a narrative arc of an unsuccessful young man who allows himself to be conned by the pyramid scheme of competing for the streets and finds his life’s purpose there (despite the fact that it ultimately turns out to be false), while the second presents a psychoanalytical fantasy about setting right a corrupt world, while forgetting about the systemic nature of social injustice. So, while Travis from No More Heroes continues in the endless vicious circle of adrenaline rushes despite their obvious falsehood (as a way of escaping the “reality” in which he is a nobody), the protagonists of Persona 5 set corrupt politicians straight and attempt to resolve the apathy of civil society, but still they remain caught in the irreconcilable competition between work, fun, and the need to spend their time effectively. This insinuates that it is not the system itself that is flawed, but only those who use it unfairly.

What’s the difference between a quest and a to-do list?

Bailes maps these four games onto four approaches to the present: hedonism, cynicism, escapism, and reformism. He thus shows the allegorical strengths for video games that are capable of capturing the social zeitgeist by means of creating virtual spaces. Except for the example of Grand Theft Auto (where Bailes considers the critique of capitalism to be a mere marketing ploy), these social allegories do not consciously appear in the games. Much like the rest of pop culture, they simply reflect the social reality of their creators. According to Bailes, however, games are still able through their interactive nature to reflect this reality in a different way than books or films. After all, games are sometimes compared to the rules of neoliberal capitalism itself – playing by the game’s rules and making gold does have a lot in common with paying rent and keeping work contracts.

Saints Row

In his short book, Bailes shows that even mainstream videogames can carry a strong political message. Not only does Bailes translate the tradition of critical theory (and psychoanalysis) to the world of gaming, but in stead of the much more politically active scene of independent video game production, he focuses on triple‑A titles with immense budgets. Just as we must talk about Avengers, we must also not forget about GTA or Saint’s Row.

In conclusion, it is necessary to note just how each of the games discussed draws attention to the structural problems of the contemporary world. And although it doesn’t offer productive correctives (Bailes is very vocal about the lack of utopian thinking here), this “incompleteness, rather than any political ideal, […] functions as a demand for a deeper social critique and more convincing answers.”

COVER PIC Šimon Chovan

TRANSLATION Vít Bohal