|

|

Translated by Lucia Udvardyová

Michal Murin is mostly known as a performer and intermedia artist. For over two decades he has been a core member of the Transmusic Comp. and the Society for Non-conventional Music. Today he heads two new media departments in the art academies in Banská Bystrica and Košice. We talk about his early works, historization of media art, and he takes us on an adventurous tour through the Slovak media culture of the 1990s.

Michal Murin, Self-Portrait, 2012.

What role does history of art, theatre and music have for you as a creator? Can you recollect the moment when you started to take into consideration what was done before in your work? What importance do you ascribe to history in artistic creation?

In 1982 I realized that everything I’d been doing and thinking about was connected to contemporary art – the art that followed the Sixties. While living in Czechoslovakia during its Normalization period, I gradually started sourcing information about 1960s art (Hudba dneška, Ladislav Kupkovič et al) at the music department of the University Library in Bratislava. Later I would learn about contemporary music each Friday from Peter Machajdík (1984 – 1986). I’d read Jazz – bulletin současné hudby magazine (Jazz – Bulletin for Contemporary Music) and books like Tělo, věc a skutečnost; Minimalizmus; or Grafické partitúry (Body, Object and Reality; Minimalism; Graphic Scores) published by the Jazz Section since 1983. The issue Jazz no. 25/1979, which I got hold of in 1983, featured John Cage’s The Future of Music/Credo, a text about La Monte Young and an article entitled Umění vcházi do ulic (Art Enters the Streets) about experimental and conceptual theatre productions in public space. Such fragmentary and disparate information, articles, footnotes in books about bourgeois art assured me that I was right and the world around me was isolated. This inspired me to embark on projects utilising public space, unusual ways of displaying bodies in public and intervening into everyday reality in a project spanning from 1984 to 1986 which bordered on theatrical suspense and action. I was an economist by vocation, who was interested in contemporary art. I studied a lot of from unofficial literature since I didn’t differentiate between the two. Later I was engaged in extensive correspondence with various museums, galleries, universities and magazines especially from America. As part of the self-education project Break the Curtain I sent out 250 airmail letters asking directors of modern museums and leading art personalities for any information regarding contemporary art. For instance, the director of the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) Kirk Varnedoe, whom I sent one piece in 1988 – instructions for an installation called Hommage á MOMA, thanked me in his letter and included a few art magazines. Subsequently I found out that a similar mode of correspondence education was also practiced by Milan Adamčiak and Robert Cyprich during the Sixties. Thus, initially I educated myself and tried to avoid making something that would be identical to what I had been reading about but at the same time, I cannot completely rule out any influences.

Michal Murin, Lifelong performance - concept, 1988. Text-art, art-fiction.

You have also written a lot about the history of contemporary art...

I have never distinguished between music, theatre and art within the context of contemporary art. I have always understood it as an integrating whole, an equilibrium. Thus, it was inevitable that I met Milan Adamčiak in 1987, who is a similar author, only more focused on music. In 1991, I started to think about publishing a book about the history of experimental theatre partly because I was part of such theatre - the “body motion performance group“ Balvan. Around the same time, I became influenced by the Japanese dance style Butó, Pina Bausch, Trischa Brown, Robert Wilson and others and wanted to edit an anthology of contemporary dance. I had lot of sources, sent from the US as part of my correspondence self-education as well as materials and brochures published by the US embassy in Prague during Normalization. In 1991, I started to write for the magazine Profil súčasného výtvarného umenia focusing on intermedia overlaps in art and the utilisation of computers in artistic pratice. Subsequently, I increasingly gravitated towards history, information or facts about art. For instance, I worked on a thematic issue centered around performance art and action art (1993). At that time, we begun to publish a glossary of Slovak artists and contemporary art terms in each issue which culminated in a renowned glossary. Moreover it was the publishing of the Avalanches 1990-1995 as a chronicle of an astonishingly fertile but short period, which not only includes information about our activities but also presents our starting points and historical background in which we created.

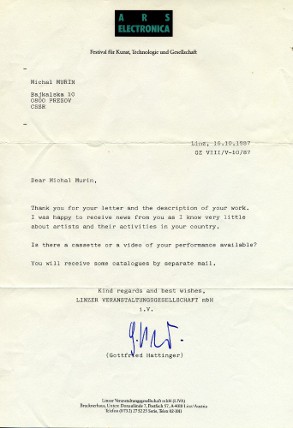

Letter describing the work sent to Ars Electronica.

| |

Letter answer from Gottfried Hattinger, AE director. |

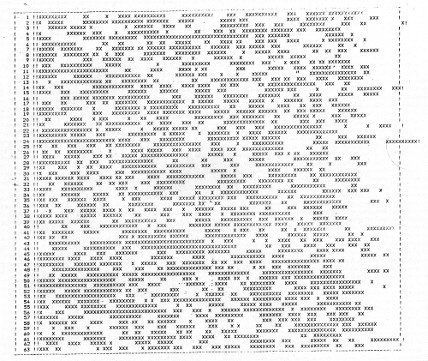

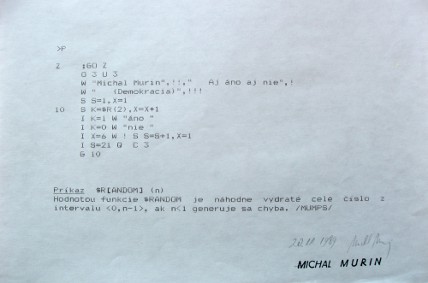

Michal Murin, 01, 1987. Project for Ars Electronica. Interactive game for a computer program, terminal displays, dot matrix printers, beeping of a monitor and people-actors.

You did a computer performance 01 at the Ars Electronica festival in 1987. Can you describe its origins?

It wasn’t performed at the festival itself but I created the work in Slovakia as a tribute to Ars Electronica. I first learned about the festival in 1984 from Peter Machajdík who had a catalogue from Ars Electronica’s Sky Art conference. A year later, in 1985, I came across Sinclair and got myself a job as a programmer. After military service, I worked on the aforementioned project. Several sources stepped in to collaborate on 01. The group Balvan had been functioning for two years already and I also had the physical set up at my disposal since I worked in a company that was equipped with a terminal network for indoor computers. Spurred on by the whirr of the stylus printers and beeps of the terminals, I created a music and motion composition for a random number generator (0,1) – (sound – silence), (motion – status) (X and space representing the void). Noise, motion, sound on one side – stalled motion, silence and void on the other. I launched the software, the printer either moved in a silent fashion or printed the letter X, the terminal beeped or stayed silent, people either moved in front of the screen, or remained still. Since I knew that such a project had little chances at the Ars Electronica competition, I sent it as a hommage to the festival director. He replied that he would like to see a video of it, but for me the mail communication sufficed. He also included two festival catalogues. In 2009, I recreated the software used for this project as a screensaver.

Michal Murin, Random Poetry, 1989. Poem realised by a computer software generating (0,1). Programmed (in MUMPS language) and printed on 20 November 1989 at MEOPTA, a state company in Rača, Bratislava. The company specialised in the military optical technics - laser pointers, lenses; its public production included the copy machines.

You are an author of several projects which encompass video, computers and internet. Towards the end of the Nineties, you wrote a critical article entitled Nové technológie v slovenskom umení alebo vyhodíme sa z kola von (New technologies in Slovak art: undermining ourselves) and subsequently edited a new media themed issue of Profil 4/2000. In the essay you implied that new media art in Slovakia at the end of 90s was still an unchartered territory. Several works and initiatives from this period, however, still slip the attention of art historians. Which of these do you consider to be worthy of a more detailed analysis or a recontextualisation?

Let me explain the events that implicated each other and generated a growing interest in new media in Slovakia and their integration in Slovak art theory. It is necessary to realize there is a prevailing animosity here towards this subject and mostly endeavours organised by professional groups are admitted into history of art, even though in the Czech Republic and Poland it is different. But let’s talk about what is part of art in general. If we manage to to incorporate video art into art and in a way seize it from audiovisual art which actually doesn’t even want it for its lack of narrative and visual experiment; if we incorporate sound into art because history of music shuns it, if visual art absorbs experimental, visual and acoustic poetry because it is not wanted by the literary circles we will be able to integrate radio art, which relies on a radio transmitter and reciever as its medium, into fine art too. It is fine art that absorbs current happenings into its scope of interest. Thus our research needs to focus on the Experimental Studio of the Slovak Radio for instance, and since 2000 also its online project RadioArt.sk, a documentation database of sound art in a context.

If this history was ever to be researched, it has to be added that apart from my correspondence (from 1987) and Machajdík’s (1985) with the Ars Electronica director, it was also Jozef Jankovič who was on a week’s trip to Linz with his computer graphics in 1989. The complete text about computer graphics in Slovakia, written by Martin Šperka, was published in the Leonardo magazine by the MIT (parts of it also appeared in Profil). At the end of 1989, I. Bertók’s and I. Janoušek’s publication Počítače a umenie (Computers and Art) came out in the Slovak Pedagogical Publishing House in Bratislava which I didn’t buy since I was somewhere else and already possessed the Ars Electronica catalogues. Wolfgang Winkler had a presentation about AE at the Festival of Intermedia Creativity (FIT) with only six people in the audience even though FIT was the most expansive event of its kind at that time with a duration of a week spread around various locations in Bratislava from the National Gallery to cafés to the desacralized church Klarisky. Chico MacMurtrie performed at the San Francisco Performance Art Festival (1991) in Bratislava a week after he triumphed at the AE with his interactive pneumatic robots. The event was reported by Kultúrny život, Profil and Slovak TV in a ten-minute documentary that I directed. New media art was derogatorily taken out of the context of fine art since concepts proved to be technologically difficult for these types of media and the thinking of artists wasn’t suited for it. This has been reiterated by the whole artistic community, rooted in the art tradition of postsocialist countries. It was deemed too technical and demonstrative, cumbersome and not conceptual enough. This is similar to Japanese new media art devoid of the experience with German hardcore concept. Even though lately Japanese interactive arts have appeared to be less infantile. Another example: I remember when Michal Bielický presented the project Exodus incorporating a GPS navigation system in an Israeli desert at AE, it was considered to be of little artistic merit but when we consider young artists working on GPS projects as part of popular culture nowadays, it is suddenly part of art. I am pleased by the shift in thinking but disappointed about the disregard for the pioneers.

In the mid-90s there were also Bee Camp and Sound Off festivals taking place.

Back in 1988 I was in touch with the post-graduate MIT student Christopher Jenney whose works only reinforced that I was on the right track in exploring new technologies in art. He was creating interactive sound and performance installations in public spaces. I had some resources from Otto Piene, the director of the Center for Advanced Visual Studies at the MIT. Whom could I only show this in Slovakia? Only to Machajdík, all the others dismissed it as some American show. He used dancers, laser scanners and it was also one of the first instances of sampling in this context. This technology was banned from being imported into Europe and its first use in Slovak art was recorded three month after its European launch in 1991 when Juraj Ďuriš and Miloš Boďa created an interactive object at a symposium in Schrattenberg in Austria. Here we also participated at a pirate radio art project which was broadcast through a home-made transmitter with a 30km range.

We shouldn’t omit Duriš‘ and Boďa’s TV video art included in the catalogue Electronic Art of the 1980s published in Canada as part of the ISEA conference. Ďuriš‘ orientation led to two years of the Bee Camp (1995, 1996) which merged several similar and simultaneous events at various places which could be some years later compared with the younger project Multiplace. It is important to take these two events seriously if only for the programme even though they do not work in the history of fine arts because it was an intermedia festival which in a way anticipated today’s multigenre and new media festivals and workshops. Alongside other intermedia festivals like Transart communication (1988), Konvergencie (1990), FIT (1991), Sound Off (1995 – 2001) and so forth, the Society for Unconventional Music (SNEH) also supported the participation of Valér Miko at Ars Electronica in the computer music section in 1994. I would also like to point out the accomplishments of Slovak composers like Ďuriš, Machajdík and Piaček at the festival of computer music in Varése in Italy. Juraj Ďuriš became a longstanding member of the jury after winning the competition several times.

Barla video journal was published around that time.

The video journal format almost bypassed Slovakia in the 80s even though it also served as alternative news source during the underground times. Video journal is a medium of utmost importance if we think about today’s activism in the arts. Since cameras were available and tapes could be played it was possible to make copies of the video footage. While in Hungary this worked – the Artpool gallery in Budapest possesses the proofs of this – in Slovakia it were largely the Hungarian influences that encouraged this format prior to 1989 and shortly afterwards. Two tapes were released about the festival in Nové Zámky - one in Paris and the other in Canada. Nevertheless, the members of Studio erté in Budapest organised presentations back in 1988. This was followed up by Peter Rónai and Miro Nicz in their project Barla five years later (1995 – 1997). There is no information about the video performances in Nové Zámky nor about the video installations presented, internet or radio art projects. For the purposes of the history of this art it is crucial that we review this because it will reveal why some artists ceased producing certain types of works and why others started to do them later with the support of art history and why they were championed as pioneers.

Martin Šperka used to organise exhibitions of computers graphics and email art as an updated version of mail art and fax art. In 1994, a special issue of Profil was published dedicated to mail art and networking as a concept championed by mail-artists which later shifted into the computer environment as net.art. Since 1995 we have featured web art in Profil. Later network projects such as Syndicate courtesy of V2 in Rotterdam, where I’ve been registered from the early on, were available. I performed at the V2 in 1999 alongside Jozef Cseres and exhibited with John Rose. In 2000 we also presented our intermedia activities at the Media Model event in Mücsarnok alongside Joszef Juhász and Peter Rónai which was organised by Miklós Peternák from C3. In the same year, the Kassák Center for Intermedia Activity (K2IC) was launched in Nové Zámky.

I think that we can also include one of new media‘s cul de sac’s – the CD-ROM - here. It would be of value to explore the first artistic projects based around the CD-ROMs. A CD-ROM catalogue entitled TransArt Communication 1995 1996 appeared in 1997, and I myself produced a CD-ROM catalogue for the exhibition Piano Hotel in Šamorín. I also prepared a multimedia presentation 15 Years of Ars Electronica, published in fragments online, for the internet magazine Inzine and its Dimension 5 CD-ROM. In 2000, a Digital Dedele CD-ROM was published by K2IC in Nové Zámky – the undertakings of this association are also worth mentioning, same as Jozef Cseres‘ publishing ventures under his nom de plume HEyeRMEarS with whom I collaborated on a well-received audio and CD ROM (one disc) bearing the name Warholes in 2003 alongside Japanese noise musicians Otomo Yosihide and Sachiko M and the Chinese DJ Mao, which sold well in Japan and Taiwan.

Even the institutionalized environment showed interest in new media and video installations. SCCA‘s annual exhibition Labyrinty (Labyrinths, 1993) in Trnava or the solo exhibitions of Peter Rónai, Jana Želibská, Peter Meluzín and other artists as well as the exhibition Video vidím – švajčiarské videoumenie (I See Video – Swiss Video Art) curated by Katarína Rusnáková at the Považská Gallery of Art should be mentioned here. The large-scale new media exhibition Butterfly Effect (1996) in Mücsarnok initiated by C3 in Budapest played a major role. C3 was established in the wake of the transformation of SCCA (Soros Center for Contemporary Art) in cooperation with a telecommunications company. Spurred on by Budapest’s lead, the Bratislava branch of SCCA shifted its focus on concept and neoconcept as demonstrated by the annual exhibition 60/90 in 1997 which interconnected the artists of the 90s with those active in the 60s through mutual collaborations whose outcome will be evident in future.

Not to forget, a large-scale multimedia performance Left Hand of the Universe held in a Synagogue in Šamorín took place simultaneously in Perth, Colorado Springs and Slovakia. We were thinking of doing live online broadcasts but at that time (November 1997) this was not possible even via the Slovak Radio.

Apart from the video performances that I had been doing I would also like to mention a seminar which we organised with Jozef Cseres under the auspices of SNEH and Department of Aesthetics at the Philosophical Faculty in Bratislava under the name New Media and Technologies in Contemporary Art and Music (1999). All this culminated in preparations of a special issue of Profil 4/2000 focused on new media, which in my opinion, was timely and passed the baton to a new generation which emerged after 2000. I then initiated the online database project @rtzoom, which eventually didn’t materialize, since I pursued the RadioArt.sk (2000) project instead. As of 2004 I have been mostly focused on introducing these art forms in the schools where I work.

Using terms intrinsic to media and digital art is fairly free and variable and is obviously related to the ongoing development in this field. What is your view of the extent to which the particular terms have been adopted by the artistic practices? How does the current Slovak history of art reflect upon them?

If we were to speak about the history of media art, we should revisit the magazine Profil (especially in the period 1991 – 1996) not only after 1999 when it was rediscovered after an almost four year hiatus in order to witness the magnificient history of the use of the terms from “computer art“ to the term I used “new technologies in art“, the introduction of the term “multimedia“ - which I didn’t use - to “new media“ applied after 1999. I started to apply the term “digital media“ after 2004. The notion “intermedia“ has a special place as an all-encompassing term - sculpting has shifted to intermedia, installations, objects, interventions, and so forth.

I’ve increasingly felt, even more so now, that the Slovník pojmov svetového a slovenského výtvarného umenia 2. polovice 20. storočia (Glossary of International and Slovak Art of the Second Half of the 20th Century, 1999) played a role in stalling the awareness of cultural and artistic communities in Slovakia about new media. It was published in a print-run of 4,000 copies and sold for ten years to students and teachers. It is without a doubt that it increased the awareness about contemporary art but it didn’t include terms such as intermedia, net.art, web art, interactive installations and other current forms of new media art. It was argued that at the time nobody did this kind of art in Slovakia anyway. This, nevertheless, changed two years later. The glossary didn’t even include the term “new media“ because it was not widely used in Slovakia then. I have come across the first utilisation of this notion in the title of the conference that I organised with Jozef Cseres in 1999. A more pronounced articulation arrived with the thematic issue of Profil 4/2000 that displayed the terminological progress of some authors (and the opposite is true with other authors).

Today we know that it was a pity not to have included these terms in the glossary. This part of art is evolving in such a way that have they developed, it would have been a great test of time – they would seem rather ridiculous and dated now. But they would have been included there at least and students would have to acknowledge them, they would become part of the general information. Many terms crucial for new media were excluded for more than 10 years from the only such glossary available. This has been partly rectified by Miloš Štofko’s glossary Od abstrakcie po živé umenie (From Abstraction to Live Art, 2007) which even mentions radio art. A glossary of new/multi/digital/trans/media and latest technologies used in artistic production could improve the status quo and has been announced since 2007 by the Prague colleagues. For now, it has to suffice that in 2011 the Slovak Radio produced a series of the first 30 entries for its Slovník výtvarného umenia show (Art Glossary) that has Mr Štofko focusing on modern art and me on intermedia, sound art, multimedia, performance art, net.art, web.art, new and digital media, etc. Further 15-minute long educational features will complement this programme.

The ten issues of the 3/4 revue magazine also played an important role in spreading the awareness. Among the publications that fill in the void are: Katarína Rusnáková’s História a teória mediálneho umenia na Slovensku (History and Theory of Media Art in Slovakia, 2006) and Rozšírené spôsoby diváckej recepcie digitálneho umenia (Expanded Forms of Audience Reception of Digital Art, 2011); two anthologies edited by Katarína Rusnáková V toku pohyblivých obrazov. Antológia textov o elektronickom a digitálnom umení v kontexte vizuálnej kultúry (Moving Pictures Flux. An Anthology of Writing about Electronic and Digital Art in the Context of Visual Culture, 2005) and Michal Murin and Jozef Cseres Od analógového k digitálnemu. Nové pohľady na nové umenia v audiovizuálnom veku (From Analogue to Digital: New Views on New Media in an Audiovisual Era, 2010).

January 2012

|